Scott H. Buck, MD

- Associate Professor of Pediatrics

- Division of Pediatric Cardiology

- The North Carolina Children? Heart Center

- University of North Carolina School of Medicine

- Chapel Hill, North Carolina

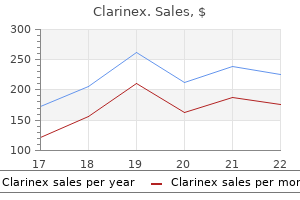

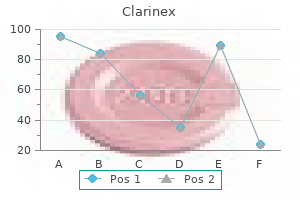

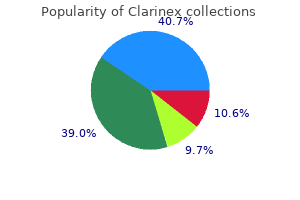

Meri Ophthalmology allergy symptoms 2013 buy cheap clarinex 5 mg, Oslo University Hospital allergy shots help asthma generic 5 mg clarinex with amex, Oslo allergy medicine over the counter non drowsy generic clarinex 5mg without a prescription, Ophthalmology allergy symptoms of gluten purchase clarinex uk, Massachusetts Eye and Ear Vattulainen allergy forecast rochester mn purchase clarinex 5 mg overnight delivery, T allergy treatment kinesiology discount 5mg clarinex free shipping. Mary Ann Conservation Mechanisms in Cultured Sheets Stem Cell Defciency and Neovascularization. Low Vision Group / Visual Psychophysics/ cells and organ-cultured diabetic corneas for 1, 2 3 Bagherinia, A. Department Ophthalmology, University of Illinois at Chicago, Victoria, Australia; 2Bionic Eye Technologies, Inc. Huiyu Biosciences, Latrobe University, Bundoora, Victoria, Australia; 5Department of Ophthalmology, cell function in healthy and diabetic cornea. Department of Ophthalmology and Visual 1 1 University of Bonn, Bonn, Germany; 6L V Prasad Aleksandra Leszczynska, M. Stout, 3 1 1 1 1, 3 Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, University of Department of Electrical and Electronic M. Choi, 8 1 1 1 4 Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada; Department Engineering, Jerusalem College of Technology, L. Hirota, 4 of Ophthalmology & Visual Sciences, University 2 2 3 1 Institut de la Vision, Sorbornne Universites, Paris, 12 H. Trainees, students and junior faculty will beneft from this unique opportunity to network and gain valuable information from those who have been in your shoes! This very popular program offers informal discussions over breakfast on a wide range of topics to provide personal guidance, insight and skills to help you advance your career! Topics will focus on professional development, career guidance, and best practices of interest to basic and clinical trainees and clinician-scientists. A number of the roundtable topics will be specifcally tailored to the needs of clinician-scientists. Lorie St-Amour, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada; 6Population Health, Singapore J. Science, Friedrich-Alexander-Universitat Erlangen University, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia; Afshari. Netherlands; Ophthalmology, Radboud University and Informatics, University of Pennsylvania, 1 2 1 1 5 Bonfglio, M. Pavlou1, Seng Hospital, Singapore, Singapore; 2Department Western Australia, Perth, Western Australia, I. Osamah Saeedi1, (Centre for Vision Research), Westmead Hospital) Photoreceptor Survival in Mouse Models of B. Tsai1, and Westmead Millennium Institute, Westmead, 1 3 1 New South Wales, Australia; 7Melbourne School Retinitis Pigmentosa. Cardiff, England, United Kingdom; 2School of Biochemistry/Molecular Biology Gesualdo3, S. Connectomics, Korea Institute of Science and and Division of Preventive Ophthalmology, Guy. Bonilha complement C3 activation in models of macular Assitance Publique Hopitaux de Paris, Paris, France 1, 2 1, 3 degeneration. Shuster2, Sciences, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Department of Regenerative Medicine, Tongji Eye E. Mohamed1, 2, 1Ophthalmology and Vision Science, University potential role of age-related synuclein in the 1 S. Franziskus Hospital Munster, Munster, (the Republic of); 2 University of Ulsan College of Stepicheva1, S. Germany; 5Faculty of Medicine, University of 3 2 2, 1 1 Medicine, Ulsan, Korea (the Republic of); College S. Mukherjee, Ophthalmology, University of Pittsburgh School of Reproductive Medicine and Andrology, Wesfalian N. Aleksander Ireland, Belfast, Northern Ireland, United Institute, the Johns Hopkins University School of Tworak1, C. Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Neuroscience, Cell Biology & Anatomy, the Zhang, A. Department of Medicine Huddinge, Center for retinal pigment epithelium in the mouse. State Key Laboratory of Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden; Department of 2 2 2 1 Chrenek, J. Pham, Astronomy, Texas A&M University, College Station, Yamaguchi, Japan; 2Kyushu University School of 4 Z. Ishikawa, Biology, University of Iceland, Reykjavik, Iceland; 2, 3 1 4 mitochondrial dynamics in the retinal pigment D. Ophthalmology, Doheny Eye Clinical Neurosciences, St Erik Eye Hospital, 1 1, 2 2 epithelium. Epithelial Cells: An Alternative Metabolic Semmelweis University, Budapest, Hungary 1 1 1 Wils, J. Netherlands; Institute of Cellular and integrative 1 1 1 1 Mitochondria Depletion and Rescue by Platelet Schulz, I. Biochemistry, University Astrophysics, Optics and Electronics, Tonantzintla, Cepko1, 2, D. Ophthalmology, University of intraocular pressure in open angle glaucoma Winterbottom2, A. Andre Costa Dublin, Dublin, Ireland 3 2 2 2 University Eye Clinic, Dipartimento di Scienze Brito, R. Metz, Psychiatry, University of Illinois at Chicago, 3 3 Korea (the Republic of); Hanyang University M. New England College of 1 1 2, 3 and Behavioral Medicine, Wake Forrest University Adrienne Ng, A. Clinic, Tajimi, Japan; Topcon Corporation, Tokyo, and Applied Informatics, Nicolaus Copernicus Japan; 4Santen Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan M. Ophthalmology, Massachusetts Eye and through a novel deep neural network model for Martini, M. Sciences and Public Health, University of Brescia, London, United Kingdom Yu-Chieh Ko1, 2, S. Cheng, 1, 2 1, 2 1 HsinChu, Taiwan utilizing the Glaucoma Score versus automated T. Singapore Eye Research grading of fundus photographs to detect Institute, Singapore National Eye Centre, glaucomatous eyes. Outcomes from a School-Based Vision Screening Superior to that of Retinal Nerve Fibre Layer Jihyun Kim1, 2, N. Alexandria University, Alexandria, Egypt; 3Institute affliated hospital of Fujian Medical University, Ryu Iikawa, T. Chang3, due to trachoma among school children in a glaucoma: diagnostic utility of 10-2 visual felds S. Fernandes1, Univ of Med, Kyoto, Kyoto, Japan; 2Biomedical Moderator: Debarun Dutta M. Ontario, Canada; 2Ophthalmology, University of (the Republic of); 2Ophthalmology, Seoul National Sakumoto1, M. Matsuo1 2 1, Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; 3Ophthalmology, University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea N. An Department of Ophthalmology, David Geffen Shenzhen Eye Hospital, Sh, China electrophysiology and psychophysical study. School of Optometry and Visual Science, treatment of strabismic amblyopia using 3D distribution of eye care providers and rates of 1 1 University of New South Wales, Sydney, New 1 video games. Optometry and Visual Sciences, City University Research Data Into Actionable Steps. Mei Ying Boon, perceptual training in adults with anisometropic 4 2, 1 3 1 Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 1 2 H. Arshad, General Psychology, University of Padova, Padova, 3 1, 2 1, 2 3 1 3 London, United Kingdom; Department of Surgery L. Wen Wen1, and Strabismic Ophthalmology, Park Road Eye, Status With Global and Regional Burden of Eye S. Rohan1, Psychology & Neuroscience, Dalhousie University, informs screening criteria. Dpt Ophthalmology, acuity deterioration 15 years after occlusion 3 1 Jerusalem, Israel; Jerusalem District Health Offce, University Lausanne, Jules-Gonin Eye Hospital, therapy for amblyopia. Ophthalmology, Juntenndo University, Ophthalmology and Vision Sciences, the Hospital Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo, Japan; 2Ophthalmology, Asama Organization, Inc. Epidemiology, Diagnosis and Outcomes estimating measures from visual function Noel A. Maria Eugenia Inga, Search Electronic Health Records to Identify Flinders University, Adelaide, South Australia, 1, 2 J. Stein, Australia; Elite School of Optometry, Chennai, 1 1 1 1 Aires, Argentina 3 M. Sangiovanni2, Chinese Medicine, Chiayi Chang Gung Memorial of Ophthalmology Connaught Hospital, Sierra M. Department of Ophthalmology, Technische 2Ophthalmology, Naresuan University, Muang, Indian population. Ophthalmology, Kyorin 1 2 3 London, United Kingdom; 2Queen Mary University University, Mitaka, Tokyo, Japan study. School of Medicine, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo, Japan; Prognosis in Dengue Uveitis in Singapore over 1Department of Ophthalmology, Sahlgrenska 2Ophthalmology, Ozenji Park Clinic, Kawasaki 12 Years. Teoh1 2, 1, University Hospital, Molndal, Sweden; 2Department city, Kanagawa, Japan; 3Ophthalmology, Nerima S. Henry1, 2, immunodefciency virus infected patients for Ocular Sarcoidosis Proposed by International M. Takase2, fbrosis in patients with Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Markham, Ontario, Canada; 2Ophthalmology, M. Cheja-Kalb2, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, 1Ophthalmology, Tokyo Metropolitan Health and L. Crane, infammation correlates with genomic bacterial 2, 1 1 University Hospital Cochin, Paris, Paris, France 1, 2 D. Ophthalmology, University of Illinois at and Visual Outcomes in Retinal Vasculitis. Ferguson3, Infammation in Chronic Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Ophthalmology, Shiley Eye Institute, Univ. National Deffence Medical Collage, Yat-Sen Memorial Hospital, Guangzhou, China; equipped with a lock-in amplifer for 3 Namiki, Saitama, Japan Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, measurement of aqueous fare. Nethralaya, Chennai, India; 2Optometry, Indiana macular reattachment with Optical Coherence Lynn K. Gonzalez Trust, Maidstone, Kent, United Kingdom; 2Kent Moderators: Ian Han and Amin Kherani Salinas, H.

Primary tumors that commonly metastasize to the nervous system are listed in Table 201-1 allergy medicine names 5mg clarinex free shipping. In approximately 10% of pts allergy testing state college pa order clarinex 5 mg visa, a systemic cancer may present with brain metastases; biopsy of primary tumor or accessible brain metastasis is needed to plan treatment allergy symptoms to gluten purchase clarinex 5mg on line. Systemic chemotherapy may produce dramatic responses in rare cases of a highly chemosensitive tumor type such as germ cell tumors allergy symptoms to condoms cheap clarinex line. Leptomeningeal Metastases Presents as headache allergy symptoms to eggs 5 mg clarinex overnight delivery, encephalopathy allergy shots mercury order genuine clarinex online, cranial nerve or polyradicular symptoms. Back pain (>90%) precedes development of weakness, sensory level, or incontinence. Medical emergency; early recognition of impending spinal cord compression essential to avoid devas tating sequelae. Progressive radiation necrosis is best treated palliatively with surgical resection unless it can be managed with glucocorticoids. Etiology is thought to be autoim mune, with susceptibility determined by genetic and environmental factors. Some pts have symptoms that are so trivial that they may not seek medical attention for months or years. Most com mon are recurrent attacks of focal neurologic dysfunction, typically lasting weeks or months, and followed by variable recovery; some pts initially present with slowly progressive neurologic deterioration. Optic neuritis can result in blurring of vision, especially in the central visual field, often with associ ated retroorbital pain accentuated by eye movement. Involvement of the brainstem may result in diplopia, nystagmus, vertigo, or facial pain, numb ness, weakness, hemispasm, or myokymia (rippling muscular contractions). Check for abnormalities in visual fields, loss of visual acuity, disturbed color perception, optic pallor or papillitis, afferent pupillary defect (paradoxical dilation to direct light following constriction to consensual light), nystagmus, internuclear ophthalmoplegia (slowness or loss of adduction in one eye with nystagmus in the abducting eye on lateral gaze), facial numbness or weakness, dysarthria, weakness and spasticity, hyperreflexia, ankle clonus, upgoing toes, ataxia, sensory abnormalities. Sagittal T2-weighted fast spin echo image of the thoracic spine demonstrates a fusiform high-signal-intensity lesion in the midthoracic spinal cord. Fin olimod In tolra n t or Id n tify n tre t n y poorre spon se un rlyin in fe tion ortra uma lin lor o G ood In tolra n t or I ha n ha n re spon se poorre spon se on sid r xw ith on of the follow in: C on tin ue pe riod 1. First-degree heart block and bradycardia can occur with fingolimod, necessitating the prolonged (6-h) observation of pts receiving their first dose. Although approved for first-line use, the role of fingolimod in this situation has yet to be defined. Regardless of which agent is chosen first, treatment should probably be altered in pts who continue to have frequent attacks. Approximately 15% of pts receiving glatiramer acetate experience one or more episodes of flushing, chest tightness, dyspnea, palpitations, and anxiety. Plasma exchange has also been used empirically for acute episodes that fail to respond to glucocorticoids. Prophylaxis against relapses can be achieved with mycophenolate mofetil, rituximab, or a combination of glucocorticoids plus azathioprine. No controlled trials of therapy exist; high-dose gluco corticoids, plasma exchange, and cyclophosphamide have been tried, with uncertain benefit. Fever, headache, meningismus, lethargy progressing to coma, and seizures may occur. Key goals: emergently distinguish between these conditions, identify the pathogen, and initiate appropriate antimicrobial therapy. Nuchal rigidity is the pathognomonic sign of meningeal irritation and is present when the neck resists passive flexion. Listeria monocytogenes is an important consideration in pregnant women, individuals >60 years, alcoholics, and immunocompromised individuals of all ages. Enteric gram-negative bacilli and group B streptococcus are increasingly common causes of meningitis in individuals with chronic medical conditions. Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase-negative staphylococci are important causes following invasive neurosurgical procedures, especially shunting procedures for hydrocephalus. Clinical Features Presents as an acute fulminant illness that progresses rapidly in a few hours or as a subacute infection that progressively worsens over several days. The classic clinical triad of meningitis is fever, headache, and nuchal rigidity (stiff neck). Alteration in mental status occurs in >75% of pts and can vary from lethargy to coma. Methicillin-sensitive Nafcillin Methicillin-resistant Vancomycin Listeria monocytogenes Ampicillin + gentamicin Haemophilus influenzae Ceftriaxone or cefotaxime or cefepime Streptococcus agalactiae Penicillin G or ampicillin Bacteroides fragilis Metronidazole Fusobacterium spp. Prognosis Moderate or severe sequelae occur in ~25% of survivors; outcome varies with the infecting organism. Common sequelae include decreased intel lectual function, memory impairment, seizures, hearing loss and dizziness, and gait disturbances. Fever may be accompanied by malaise, myalgia, anorexia, nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain, and/or diarrhea. A mild degree of lethargy or drowsiness may occur; however, a more profound alteration in consciousness should prompt consideration of alternative diagnoses, including encephalitis. The incidence of enteroviral and arboviral infections is greatly increased during the summer. As a general rule, a lymphocytic pleocytosis with a low glucose concentration should suggest fungal, listerial, or tuberculous meningitis or noninfectious disorders. Clinical features are those of viral meningitis plus evidence of brain tissue involvement, commonly including altered consciousness such as behavioral changes and hallucinations; seizures; and focal neurologic findings such as aphasia, hemiparesis, involuntary move ments, and cranial nerve deficits. Etiology the same organisms responsible for aseptic meningitis are also responsible for encephalitis, although relative frequencies differ. Note the area of increased signal in the right temporal lobe (left side of image) confined predominantly to the gray matter. This pt had predominantly unilateral disease; bilateral lesions are more common, but may be quite asymmetric in their intensity. Predisposing conditions include otitis media and mastoiditis, paranasal sinusitis, pyogenic infections in the chest or other body sites, head trauma, neurosurgical procedures, and dental infections. In Latin America and in immigrants from Latin America, the most common cause of brain abscess is Taenia solium (neuro cysticercosis). Clinical Features Brain abscess typically presents as an expanding intracranial mass lesion, rather than as an infectious process. The classic triad of headache, fever, and a focal neurologic deficit is present in <50% of cases. Significant sequelae including seizures, persisting weakness, aphasia, or mental impairment occur in 20% of survivors. In addition, there are characteristic cytologic alterations in both astrocytes and oligodendrocytes. Pts often present with visual deficits (45%), typically a homonymous hemianopia, and mental impairment (38%) (dementia, confusion, personality change), weakness, and ataxia. These lesions have increased T2 and decreased T1 signal, are generally nonenhancing (rarely they may show ring enhance ment), and are not associated with edema or mass effect. Pleocytosis occurs in <25% of cases, is predominantly mononuclear, and rarely exceeds 25 cells/ L. In the first, symptoms are chronic and persistent, whereas in the second there are recurrent, discrete episodes with complete resolution of meningeal inflammation between episodes without specific therapy. In the latter group, likely etiologies are herpes simplex virus type 2, chemical meningitis due to leakage from a tumor, a primary inflammatory condition, or drug hypersensitivity. Imaging studies are also useful to localize areas of meningeal disease prior to meningeal biopsy. A meningeal biopsy should be considered in pts who are disabled, who need chronic ventricular decompression, or whose illness is progressing rapidly. Tuberculosis is the most common condition identified in many reports outside of the United States. In approximately one-third of cases, the diagnosis is not known despite careful evaluation. A number of the organisms that cause chronic meningitis may take weeks to be identified by culture. It is reasonable to wait until cultures are finalized if symptoms are mild and not progressive. However, in many cases progressive neurologic deterioration occurs, and rapid treatment is required. Empirical therapy in the United States consists of antimycobacterial agents, amphotericin for fungal infection, or glucocorticoids for noninfectious inflammatory causes (most common). Carcinomatous or lymphomatous meningitis may be difficult to diagnose initially, but the diagnosis becomes evident with time. Nerve involvement may be single (mononeuropathy) or mul tiple (polyneuropathy); pathology may be axonal or demyelinating. If only weakness is present without any evidence of sensory or autonomic dysfunction, consider a motor neuropathy, neuromuscular junction disorder, or myopathy; myopathies usually have a proximal, symmetric pattern of weakness. Polyneuropathy involves wide spread and symmetric dysfunction of the peripheral nerves that is usually distal more than proximal; mononeuropathy involves a single nerve usually due to trauma or compression; multiple mononeuropa thies (mononeuropathy multiplex) can be a result of multiple entrap ments, vasculitis, or infiltration. Ye s o M on on uropa thy on on uropa thymultiplx olyn uropa thy va lua tion of othe r isord ror re ssura n n E x x x follow up Isthe lsion xon l xon l mye lin tin xon l mye lin tin or mye lin tin Consider in pts with a slowly progressive distal weakness over many years with few sensory symptoms but significant sensory deficits on clinical examination. Based on the answers to these seven key questions, neuropathic dis orders can be classified into several patterns based on the distribution or pattern of sensory, motor, and autonomic involvement (Table 205-1). An oral glucose tolerance test is indicated in pts with pain ful sensory neuropathies even if other screens for diabetes are negative. Diagnostic tests are more likely to be informative in pts with asymmetric, motor-predominant, rapid onset, or demyelinating neuropathies. Myopathic disorders are marked by small, short-duration, polyphasic muscle action potentials; by contrast, neuropathic disorders are characterized by muscle denervation. In long-standing denervation, motor unit potentials become large and polyphasic due to collateral reinnervation of denervated muscle fibers by axonal sprouts from surviving motor axons. Proper care of dener vated areas prevents skin ulceration, which can lead to poor wound healing, tissue resorption, arthropathy, and ultimately amputation. Over two-thirds are preceded by an acute respiratory or gastrointestinal infection. Diabetic neuropathy: typically a distal symmetric, sensorimotor, axonal poly neuropathy. Other variants include: isolated sixth or third cranial nerve palsies, asymmetric proximal motor neuropathy in the legs, truncal neuropathy, autonomic neu ropathy, and an increased frequency of entrapment neuropathy (see below). When an inflammatory disorder is the cause, mononeuritis multiplex is the term used. Immunosuppressive treatment of the underlying disease (usually with glucocorticoids and cyclophos phamide) is indicated. A tissue diagnosis of vasculitis should be obtained before initiating treatment; a positive biopsy helps to justify the necessary long-term treatment with immunosuppressive medications, and pathologic confirmation is difficult after treatment has commenced. Intrinsic factors making pts more susceptible to entrap ment include arthritis, fluid retention (pregnancy), amyloid, tumors, and diabetes mellitus. Surgical decompression is considered for chronic mononeuropathies that are unresponsive to conservative treatment, if the site of entrapment is clearly defined. Characteristic distribution: cranial muscles (eyelids, extraocular muscles, facial weakness, nasal or slurred speech, dysphagia); in 85%, limb muscles (often proximal and asymmetric) become involved. Complications: aspiration pneumonia (weak bulbar muscles), respi ratory failure (weak chest wall muscles), exacerbation of myasthenia due to administration of drugs with neuromuscular junction blocking effects (quinolones, macrolides, aminoglycosides, procainamide, propranolol, nondepolarizing muscle relaxants). Postsynaptic folds are flattened or simplified, with resulting inefficient neuromuscular transmission. Muscarinic side effects (diarrhea, abdominal cramps, salivation, nausea) blocked with atropine/ diphenoxylate or loperamide if required. Immunosuppressive drugs (mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, cyclophosphamide) may spare dose of prednisone required long-term to control symptoms. An associated sensory loss suggests injury to peripheral nerve or the central nervous system rather than myopathy; on occasion, disorders affecting the anterior horn cells, the neuromuscular junction, or peripheral nerves can mimic myopathy. Any disorder causing muscle weakness may be accompanied by fatigue, referring to an inability to maintain or sustain a force; this must be distinguished from asthenia, a type of fatigue caused by excess tiredness or lack of energy. Fatigue without abnormal clinical or laboratory findings almost never indicates a true myopathy. Muscle disorders are usually painless; however, myalgias, or muscle pains, may occur. A muscle contracture due to an inability to relax after an active muscle contraction is associated with energy failure in glycolytic disor ders. Myotonia is a condition of prolonged muscle contraction followed by slow muscle relaxation. Progressive weakness in hip and shoulder girdle muscles beginning by age 5; by age 12, the majority are nonambulatory. Diagnosis is established by determination of dystrophin deficiency in muscle tissue or mutation analysis on peripheral blood leukocytes.

Discount clarinex 5 mg mastercard. Avoiding This Season's 'Pollen Tsunami'.

Although they are less in uential allergy testing yakima wa effective 5 mg clarinex, each factor may still make a student think twice about committing to one specialty or another allergy symptoms pregnancy clarinex 5 mg cheap. When contemplating a possible specialty allergy treatment seasonal buy cheap clarinex 5 mg, keep the following 10 vari ables in mind allergy symptoms images buy clarinex discount, determine their order of importance allergy forecast waco texas purchase clarinex 5mg mastercard, and apply them to each eld you are considering allergy medicine ranking purchase clarinex 5 mg. Before committing to a specialty, future physicians rst need to decide what type of doctor they would like to become. The generalist specialties are those in which physicians practice primary care medicine. Classically, these have always included family practice, internal med icine, and pediatrics. For many, psychiatrists and obstetrician-gynecologists also fall within this category. All generalists have broad medical knowledge, encom passing a variety of common (and often chronic) problems in their community. An integral part of their patients lives, they provide long-term continuous care in a single setting, referring their patients to specialists only when necessary. As the rst doctor to see a patient, a generalist must have greater tolerance for the unknown, especially when dealing with signs and symptoms that may not fall into a neat diagnosis. Swamped with dozens of medical journals, they need to read daily to keep up with the latest advances in their elds. Although pediatrics, for instance, is still considered a specialty, a true spe cialist, by de nition, cares for a speci c region of the body or a narrowly de ned area of medicine. As practitioners of secondary or terti ary care medicine, specialists prefer action-oriented patient interactions. Within their narrow scope of practice, they perform many technical procedures, like cataract surgery or cardiac catheterization. Radiology, physical medicine and rehabilitation, pathology, anesthesiology, radiation oncology, emergency medicine, and nuclear medicine fall within this category. Although not front-line doctors, these physicians still play a cru cial role in patient care. Without them, patients would not make it through sur gery alive, receive accurate diagnoses from imaging and biopsy studies, or receive the correct doses of radiation therapy to treat their cancer. Because of their anony mous roles and minimal patient contact, these behind-the-scenes doctors tend not to get the recognition they deserve from their patients. Without external re wards, they instead have to derive their professional satisfaction from within. Because the subject matter and type of patient care differs quite a bit across the specialties, every doctor practices a distinctive brand of medicine. Lying on the opposite ends of the specialty content/patient care spectrum, these two elds almost seem like completely different professions! At the most fundamental level, with all other factors aside, medical students should love the intellectual content of their specialty. To gauge the appeal of the clinical problems found in a specialty, read the current literature for 1 week. If you love clinical pharmacology and physiology, then perhaps a career in anes thesiology is your destiny. If studying anatomy brings up bad memories from your rst year of medical school, then stay away from surgical specialties, radiology, and pathology. After much de liberation, you will become aware of feeling at home in certain elds of medi cine. Those that like immediate interventions, technical skills, and urgent prob lems nd themselves drawn to surgical specialties or medical subspecialties. Students who prefer lots of interpersonal contact, a diverse patient population, and preventive medicine usually select a primary care specialty. Yet until medical students nally spend hours with patients in the hospital while on clinical rotations, they really have no idea what this experience is like. Most love talking with patients, form ing relationships with them, and examining them for signs of disease. Others, however, nd that interacting with sick people is less appealing than they had imagined. They do not like performing physical examinations, for example, or dealing with gushes of body uids or the smell of infected wounds. No matter what your colleagues might say, wanting a specialty with more (or less) patient contact has no bearing on how good a physician you will be. Radiologists and pathologists, who have basically no contact with pa tients, are equally as righteous doctors as internists, who interact with and exam ine patients in every single encounter. Every specialist or subspecialist has an im portant role in patient care; some just have more face time with patients than others. You should decide how much patient contact you want in your career and rule out specialties that may not meet your needs. If long-term relationships and continuity of care are important, consider areas like internal medicine and fam ily practice. If you like getting down and dirty, think about careers in emergency medicine, obstetrics-gynecology, and surgery. In some specialties, like urology and orthopedic surgery, doctors only have to perform focused physicals (instead of examining everything). In elds like emergency medicine and anesthesiology, con tact with the patient is typically short and to the point. Emergency medicine physicians, for instance, are always dealing with many angry patients with nonemergent complaints who have been kept waiting for hours on end. Pe diatricians have to interact with demanding, concerned parents in addition to sick infants and children. Oncologists (medical, surgical, and radiation) have patients with mortal diseases that typically lead to poor outcomes despite aggressive treat ment. Obstetricians manage a highly litigious group of patients who could slap them with a malpractice suit for any minor defect in their baby. Although these examples seem like stereotypes, the maxim that all doctors are not equal also holds true for their patients. Think about the areas of medicine in which you are the happiest and forget about how others (fam ily, friends, and colleagues) might view your chosen specialty. Always remem ber that every type of doctor has an important role in the big picture of medi cine, and the idea that one specialty garners more respect and prestige than another is really just a matter of personal opinion. Because all medical students have excelled academically their entire lives, those who subscribe to these be liefs nd it hard at this point to stop being the best. For them, a career in fam ily practice or psychiatry may not carry as much social status as being a world renowned neurosurgeon or earning a position in ophthalmology, an ultracompetitive specialty. By putting aside external in uences such as social pres tige and others expectations, you will likely choose the right specialty and end up a much happier doctor. After working long hours in the hospital or clinic, physicians end up taking calls in the middle of the night to deliver a baby, remove an appendix, or admit a patient. Com pared to previous generations of physicians, the millennium medical student seeks a much better balance between life and work. They desire less night call, fewer hours spent in the hospital, and more control over their work schedules. Many are even willing to give up income and professional aspirations to have bet ter personal lives and more free time. The current focus is now shifting to spe cialties with more controllable lifestyles and higher incomes relative to the length of training. What accounts for the higher priority of quality-of-life issues in a medical ca reer The dean at one prestigious medical school believes that the change mir rors a general shift in societal values and professional goals. Delayed grati ca tion and unremitting toil were the rules of the day, and residency programs were built on that model. But young people coming through now want to spend more time with their families, she commented. Today nearly half of all graduating doctors are women, most of whom want exible careers with time to raise children and maintain a nor mal family life. Many older students left behind careers in business and technology, where they could have earned more money with much less stress. For them, medicine, once aspired to as both a noble profession and a guarantee of nan cial security, strikes many current students as simply a stressful and poorly-paid job. Certain areas of medicine, particularly the primary care specialties, have more of these problems than others. Medical stu dents, therefore, are turning to specialties that afford better lifestyles and mini mal hassles. As medical students reject elds with more grueling lifestyles (like internal medicine and obstetrics-gynecology), one workaholic specialty is par ticularly suffering: general surgery. A highly competi tive specialty for decades, general surgery is the gateway to high-status careers in vascular, cardiothoracic, oncologic, and plastic surgery, among others. The poor quality of life and years of personal sacri ce are discouraging many top medical students from surgical careers. So which are the so-called lifestyle specialties that the most academically suc cessful students are selecting They include radiology, dermatology, emergency medicine, anesthesiology, pathology, ophthalmology, physical medicine and re habilitation, and neurology (among others), all of which allow you to control the number of hours you devote to your practice. You could potentially have a career with adequate family and leisure time, less stress, a more regular schedule, and an income commensurate to the workload. The evidence is in the numbers: in 2002, the ll rate of programs in anesthesiology and physical medicine and rehabilitation increased by 7% and 13%, respectively. Within this spectrum, 4 to 5 years of residency training are necessary for careers in anesthesiology, pathology, dermatology, and radiology, for example. If you want to become a subspecialist, plan on adding even more years of training in a fellowship. Cardiologists, for instance, spend a total of 6 years learning the discipline before entering practice (a 3-year internal medicine residency plus a 3-year fellowship). Yet some medical students are more concerned than others about the number of years residency training requires. Tired of delayed grati cation, these students are quite anxious to nish training, practice medicine unsupervised, and start earn ing a real salary. Others simply want to nish training so they can devote time to outside interests. In any case, never forget that the arduous, low-paying years of residency and/or fellowship are only temporary. Medical students should not select a less-preferred specialty just because the residency training is shorter. Because entrance into certain specialty programs is much more dif cult than others (see Chapter 11), medical students must be well aware of their chances. Unfortunately, just because your heart is set on becoming a plastic sur geon or an ophthalmologist does not necessarily mean it will be possible. But medical students should not base their decisions on predictions such as, I can only match into pediatrics, or Im not going to bother with radiation oncology because I know I wont get into it. Compare the difficulty of obtaining a training position in that specialty with your chances of matching into it. Medical students interested in highly competitive specialties need a great deal of exibility when making these choices. You might need a backup specialty (second or third choice option) if the eld you want is slightly beyond your academic reach. By factor ing in this less in uential variable, future physicians will match with the most ap propriate specialty. The issue of nancial rewards, therefore, becomes very important during the senior year when it comes time to select a specialty. After 4 years of paying exorbitant tuition, coupled with the prospect of many low-paying years of residency train ing, graduating physicians are very concerned about their future income poten tial. With massive amounts of debt, they often put their altruistic motives aside and focus instead on economic realities. As a result, future reimbursement is an in uential factor in some students decisions to enter a given specialty. New physicians with huge amounts of in debtedness are shunning the primary care elds because of their low earning po tential. Others want to pay off their loans right away, so they lean toward spe cialties that shell out high starting salaries, like radiology, anesthesiology, and orthopedic surgery.

Epidemiology: Retinal artery occlusions occur significantly less often than vein occlusions allergy forecast salt lake city clarinex 5 mg fast delivery. Symptoms: In central retinal artery occlusion allergy jewelry buy clarinex 5mg without prescription, the patient generally com plains of sudden allergy testing dogs blood buy clarinex 5mg overnight delivery, painless unilateral blindness allergy shots yahoo answers buy 5mg clarinex with visa. In branch retinal artery occlu sion allergy symptoms dry throat purchase 5mg clarinex with mastercard, the patient will notice a loss of visual acuity or visual field defects allergy symptoms from tree pollen buy clarinex 5 mg overnight delivery. In the acute stage of central retinal artery occlusion, the retina appears grayish white due to edema of the layer of optic nerve fibers and is no longer trans parent. Only the fovea centralis, which contains no nerve fibers, remains vis ible as a cherry red spot because the red of the choroid shows through at this site. Patients with a cilioretinal artery (artery origi nating from the ciliary arteries instead of the central retinal artery) will exhibit normal perfusion in the area of vascular supply, and their loss of visual acuity will be less. Atrophy of the optic nerve will develop in the chronic stage of central retinal artery occlusion. In the acute stage of central retinal artery occlusion, the fovea centralis appears as cherry red spot on ophthalmoscopy. There is not edema of the layer of optic nerve fibers in this area because the fovea contains no nerve fibers. In branch retinal artery occlusion, a retinal edema will be found in the affected area of vascular supply. Perimetry (visual field testing) will reveal a total visual field defect in central retinal artery occlusion and a partial defect in branch occlusion. The paper-thin vessels and ex tensive retinal edema in which the retina loses its transparency are typical signs. Treatment: Emergency treatment is often unsuccessful even when initiated immediately. Ocular massage, medications that reduce intraocular pressure, or paracentesis are applied in an attempt to drain the embolus in a peripheral retinal vessel. Calcium antagonists or hemodilution are applied in an attempt to improve vascular supply. Lysis therapy is no longer performed due to the poor prognosis (it is not able to prevent blindness) and the risk to vital tissue involved. Prophylaxis: Excluding or initiating prompt therapy of predisposing under lying systemic disorders is crucial (see Table 12. The prognosis is better where only a branch of the artery is occluded unless a macular branch is affected. Epidemiology: Arterial hypertension in particular figures prominently in clinical settings. Vascular changes due to arterial hypertension are the most frequent cause of retinal vein occlusion. Pathogenesis: High blood pressure can cause breakdown of the blood-retina barrier or obliteration of capillaries. This results in intraretinal bleeding, cot ton-wool spots, retinal edema, or swelling of the optic disk. Symptoms: Patients with high blood pressure frequently suffer from head ache or eye pain. Diagnostic considerations: Hypertensive and arteriosclerotic changes in the fundus are diagnosed by ophthalmoscopy, preferably with the pupil dilated (Tables 12. Differential diagnosis: Ophthalmoscopy should be performed to exclude other vascular retinal disorders such as diabetic retinopathy. Diabetic reti nopathy is primarily characterized by parenchymal and vascular changes; a differential diagnosis is made by confirming or excluding the systemic under lying disorder. Treatment: Treating the underlying disorder is crucial where fundus changes due to arterial retinopathy are present. The column of venous blood is constricted by the sclerotic artery at an arterio venous crossing. Clinical course and complications: Sequelae of arteriosclerotic and hyper tensive vascular changes include retinal artery and vein occlusion and the for mation of macroaneurysms that can lead to vitreous hemorrhage. In the pres ence of papilledema, the subsequent atrophy of the optic nerve can produce lasting and occasionally severe loss of visual acuity. Prognosis: In some cases, the complications described above are unavoidable despite well controlled blood pressure. Epidemiology: this rare disorder manifests itself in young children and teenagers. Pathogenesis: Telangiectasia and aneurysms lead to exudation and eventu ally to retinal detachment. Symptoms: the early stages are characterized by loss of visual acuity, the later stages by leukocoria (white pupil; see. Diagnostic considerations and findings: Ophthalmoscopy will reveal telan giectasia, subretinal whitish exudate with exudative retinal detachment and hemorrhages. Treatment: the treatment of choice is laser photocoagulation or cryotherapy to destroy anomalous vasculature. Prognosis: Left untreated, the disease will eventually cause blindness due to total retinal detachment. Infants with birth weight below 1000g are at increased risk of developing the disorder. Retinopathy of prematurity is not always preventable despite optimum care and strict monitoring of partial pressure of oxygen. Etiology: Preterm birth and exposure to oxygen disturbs the normal develop ment of the retinal vasculature. This results in vitreous hemorrhage, retinal detachment, and, in the late scarring stage, retrolenticular fibroplasia as ves sels and connective tissue fuse with the detached retina. Findings and symptoms: After an initially asymptomatic clinical course, vit reous hemorrhage or retinal detachment will be accompanied by secondary strabismus. A plus stage includes dilated and tortuous vasculature of the posterior pole in addition to the other changes. Diagnostic considerations: the retina should be examined with the pupil dilated four weeks after birth at the latest. Differential diagnosis: Other causes of leukocoria such as retinoblastoma or cataract (see Table 11. Prophylaxis: Partial pressure of oxygen should be kept as low as possible, and ophthalmologic screening examinations should be performed. This can be classified into four types: O Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment results from a tear, i. Blood, lipids, or serous fluid accumulates between the neurosensory retina and the retinal pig ment epithelium. In rare cases, second ary retinal detachment may also result from a tear due to other disorders or injuries. Proliferative vitreore tinopathy frequently develops from a chronic retinal detachment (see Chapter 11, Vitreous Body). Epidemiology: Although retinal detachments are relatively rarely encoun tered in ophthalmologic practice, they are clinically highly significant as they can lead to blindness if not treated immediately. Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (most frequent form): Approxi mately 7% of all adults have retinal breaks. This indicates the significance of posterior vitreous detachment (separation of the vitreous body from inner surface of the retina; also age-related) as a cause of retinal detachment. The annual incidence of retinal detachment is one per 10 000 persons; the prevalence is about 0. There is a known familial disposition, and retinal detachment also occurs in conjunction with myopia. Exudative, tractional, and tumor-related retinal detachments are encountered far less frequently. O Round breaks: A portion of the retina has been completely torn out due to a posterior vitreous detachment. This will occur only where the liquified vitreous body separates, and vitreous humor penetrates beneath the retina through the tear. The retinal detachment occurs when the forces of adhesion can no longer withstand this process. Tractional forces (tensile forces) of the vitreous body (usually vitreous strands) can also cause retinal detachment with or without synchysis. In this and every other type of retinal detachment, there is a dynamic interplay of tractional and adhesive forces. This develops from the tensile forces exerted on the retina by preretinal fibrovascular strands (see proliferative vitreoreti nopathy) especially in proliferative retinal diseases such as diabetic reti nopathy. Subretinal fluid with or without hard exu date accumulates between the neurosensory retina and the retinal pigment epithelium. Either the transudate from the tumor vasculature or the mass of the tumor separates the retina from its underlying tissue. A posterior vitreous detachment that causes a retinal tear may also cause avulsion of a retinal vessel. The patient will perceive this as black rain, numerous slowly falling small black dots. The patient will perceive a falling curtain or a rising wall, depending on whether the detachment is supe rior or inferior. A break in the center of the retina will result in a sudden and significant loss of visual acuity, which will include metamorphopsia (image distortion) if the macula is involved. Diagnostic considerations: the lesion is diagnosed by stereoscopic exami nation of the fundus with the pupil dilated. Ophthalmoscopy will reveal a bullous retinal detachment; in rhegmatogenous retinal detachment, a bright red retinal break will also be visible (see. The tears in rheg matogenous retinal detachment usually occur in the superior half of the ret ina in a region of equatorial degeneration. In tractional retinal detachment, the bullous detachment will be accompanied by preretinal gray strands. In exudative retinal detachment, one will observe the typical picture of serous detachment; the exudative retinal detachment will generally be accom panied by massive fatty deposits and often by intraretinal bleeding. The tumor-related retinal detachment (as can occur with a malignant melanoma) either leads to secondary retinal detachment over the tumor or at some distance from the tumor in the inferior peripheral retina. Ultrasound studies can help confirm the diagnosis where retinal findings are equivocal or a tumor is suspected. An inferior retinal detachment at some distance from the tumor is a sign that the tumor is malignant. Differential diagnosis: Degenerative retinoschisis is the primary disorder that should be excluded as it can also involve rhegmatogenous retinal detach ments in rare cases. Fluid accumulation in the choroid, due to inflam matory choroidal disorders such as Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome, causes the retinal pigment epithelium and neurosensory retina to bulge outward. These forms of retinal detachment have a greenish dark brown color in con trast to the other forms of retinal detachment discussed here. Treatment: Retinal breaks with minimal circular retinal detachment can be treated with argon laser coagulation. The retina surrounding the break is fused to the underlying tissue whereas the break itself is left open. More extensive retinal detachments are usually treated with a retinal tamponade with an elastic silicone sponge that is sutured to the outer surface of the sclera, a so-called budding procedure. It can be sutured either in a radial position (perpendicular to the limbus) or parallel to the limbus. This indents the wall of the globe at the retinal break and brings the portion of the retina in which the break is located back into contact with the retinal pigment epithelium. An artifical scar is created to stabilize the restored contact between the neurosensory retina and retinal pigment epithelium. Where there are several retinal breaks or the break cannot be located, a silicone cer clage is applied to the globe as a circumferential buckling procedure. The pro cedures described up until now apply to uncomplicated retinal detachments, i. Suturing a retinal tamponade with silicone sponge may also be attempted initially in a complicated retinal detachment with proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Prophylaxis: High-risk patients above the age of 40 with a positive family history and severe myopia should be regularly examined by an ophthalmolo gist, preferably once a year. Clinical course and prognosis: About 95% of rhegmatogenous retinal detachments can be treated successfully with surgery. The prognosis for the other forms of retinal detachment is usually poor, and they are often associated with significant loss of visual acuity. Pathogenesis: Idiopathic retinal splitting occurs, usually in the outer plexi form layer. The patient will usually notice a reduction of visual acuity and see shadows only when the retinal split is severe and extends to the posterior pole. Diagnostic considerations: Ophthalmoscopic examination will reveal bullous separation of the split inner layer of the retina.